Understanding the Tuna issue

Tuna is renowned for its health benefits and firm texture and is used worldwide in cooking. Nowadays, tinned tuna is the most heavily consumed seafood product on Earth. Tuna migrate long distances and live in temperate waters, but they are also caught the most: no less than 5.7 million tonnes of tuna were caught in 2019 in oceans*.

Of the 13 species that exist, seven are used commercially. In fact, 95% of the global tuna market* is met by skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus Pelamis), yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) and bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus).

The tuna we use at la belle-iloise is albacore (longfin) tuna (Thunnus alalunga), one of the smallest tuna species weighing 40 kilogrammes and measuring a maximum of 1.20 metres in length. Albacore tuna is less endangered and corresponds to 4% of the volumes of tuna caught*.

Tuna, a little-known fish up until the 20th century

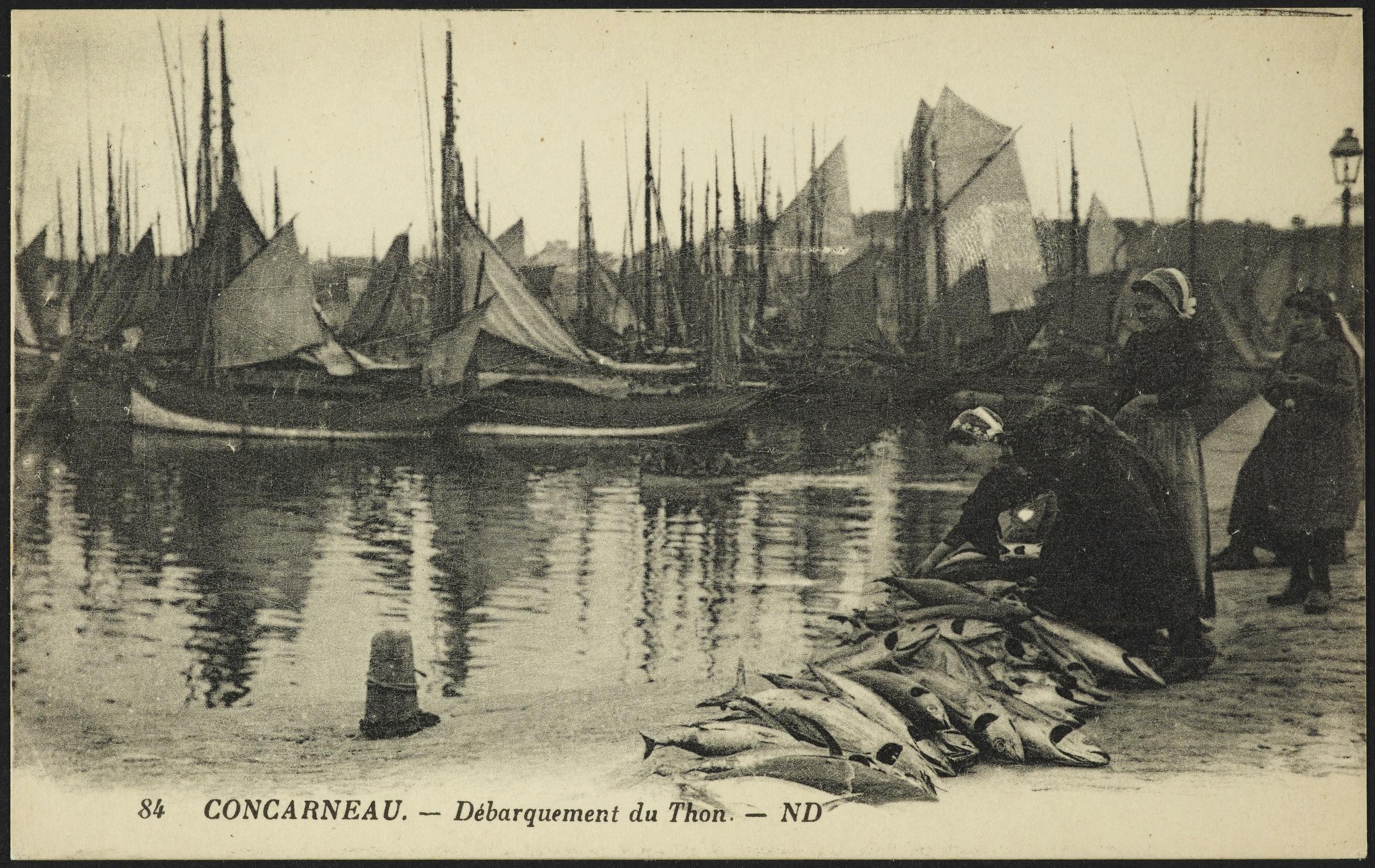

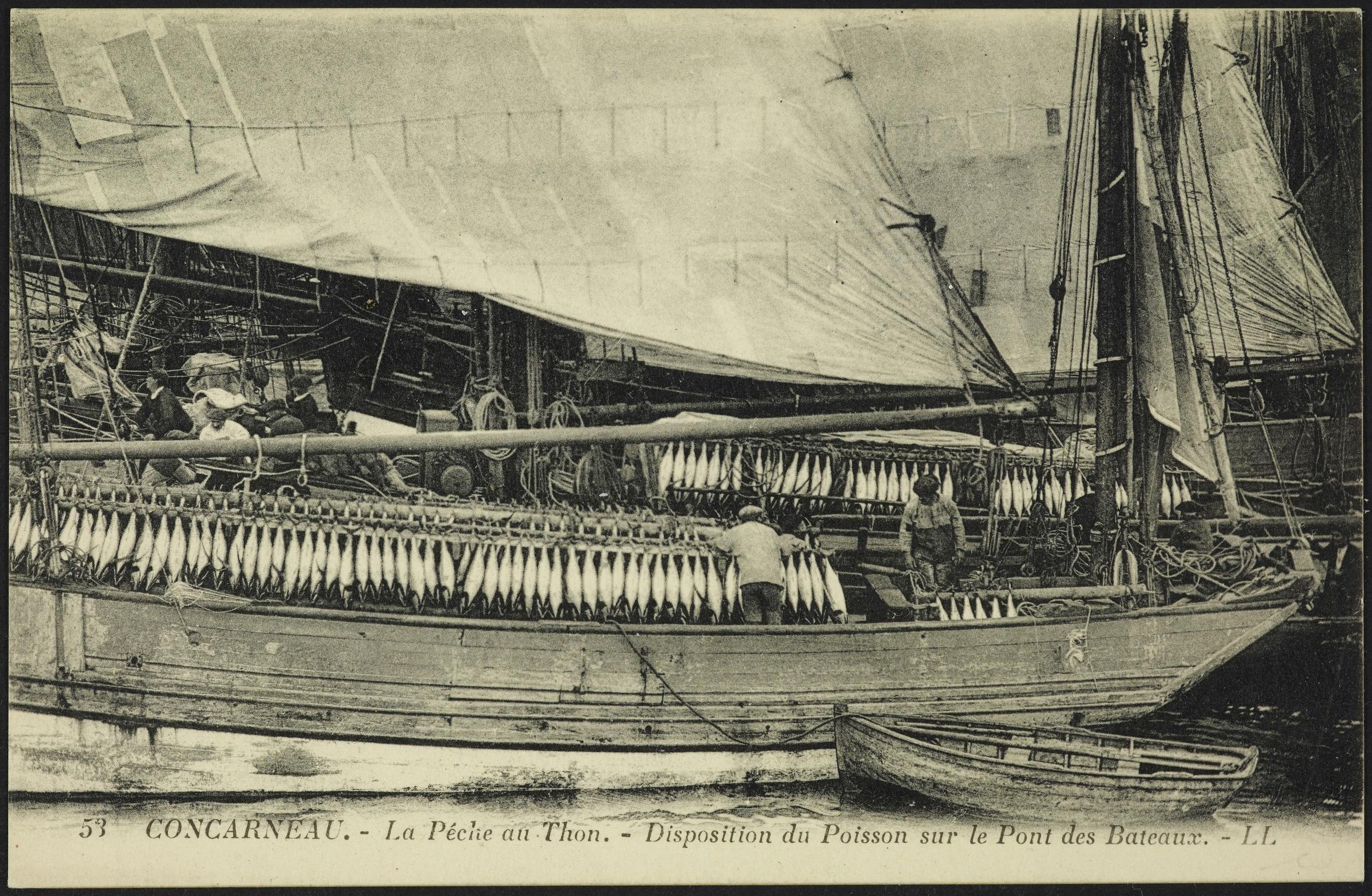

Around the world, hardly any tuna were caught or eaten before the 20th century. In France, only fishers from certain very specific regions had known about its existence for centuries: the Basques and the inhabitants of the Ile d’Yeu. They caught tuna from San Sebastian to Belle-Ile during the summer for use as winter provisions. Sliced, then covered in salt or marinated in vinegar, it was a form of sustenance during harsh winters.

The Italian zoologist Francesco Citti was the first to scientifically describe and observe the albacore tuna sighted off the coast of Sardinia in 1777. Meanwhile, the French naturalist Bonnaterre gave it the universal scientific name Thunnus alalunga in his book Ichthyologie**. The Italian term “a la lunga” means “long”, a reference to the albacore’s remarkably long pectoral fin when compared to other species. Basque fishers meanwhile used to call it “hégalalouchia”, meaning “longfin” in English. And the fishers from the Ile d’Yeu called this fish “long ear”.

In the 19th century, the fishers of Ile de Ré, Sables d’Olonne and Ile de Groix learned how to catch this fish from the Ile d’Yeu fishers they had hired for this purpose. From then, salted albacore tuna appeared alongside Mediterranean red tuna on Parisian markets. Albacore tuna started to gain in popularity due to “its generous texture”, as noted by the French anatomists Cuvier and Valenciennes in their monumental work Histoire naturelle des poissons in 1831**.

During this same period, the French invention of ‘appertisation’ (sterilisation in airtight containers) revolutionised the world of food preservation, heralding the arrival of tinned sardines. However, humankind had to wait until the 1920s to taste the first tinned longfin tuna. And it had to wait even longer, the 1950s, to enjoy the first tinned yellowfin tuna. From then on, tinned tuna’s popularity hit the roof.

Tuna, a universal food for the contemporary world

In the 20th century, tuna went from being a winter food stock of limited regional interest to a universal foodstuff. Tinned food, a major invention for humankind, became mainstream. And this paved the way for the canning and consumption of fish. Technological advances also industrialised the fishing industry, accelerating tuna catches.

As such, in 70 years, global tuna catches have risen by more than 1,000%, from 500,000 tonnes in 1950 to 5.7 million tonnes in 2019*. If you look past the success of tinned tuna and changing lifestyles, this monumental rise is also the result of the exponential growth of the world’s population, which has tripled since 1950.

Unfortunately, the tuna in tinned tuna are often caught using a fish aggregating device (FAD***). It is a method of fishing that is symbolic of contemporary society — and its faults. Today, we must set limits together and reach common ground to achieve a good balance.

Reaching an agreement for more sustainable tuna fishing and consumption

Thanks to the joint efforts of public institutions, environmental organisations, and players in the fishing industry, tuna continues to be available to this day in most FAO zones. What’s more, 65% of tuna stocks are caught in a sustainable manner*. However, 35% of tuna stocks continue to be overexploited*, a figure that is too high, relatively constant, and does not fall in at-risk areas.

The core issue is excess. Fishing and catching the correct amount of tuna —only what you need on a daily basis and in the areas in which stocks are at satisfactory levels— is the first rule that everyone needs to meet to eradicate overfishing.

This does not mean you should stop eating tuna. Instead, the focus should be on more intelligent fishing and consumption. This is a work in progress, a collective undertaking with the United Nations, public institutions, scientists, fishers, environmental organisations and everyone involved in fisheries, including canneries, and consumers, too.

La belle-iloise albacore tuna: a guarantee of exception

Our albacore tuna is always caught without the use of FADs***, when the fish are mature and outside of reproduction periods. We can prove this as our specifications prevent us from buying tuna that weigh less than 8 kilogrammes, which scientists consider juvenile. As the tuna will not have reproduced yet, catching them when less than 8 kilograms would prevent the replenishment of the next generation.

La belle-iloise is keenly aware of our impact, and we are determined to do things right. This purchasing policy sets us apart from most other buyers. Our code of practice calibrates tuna into three sizes: 0–4 kg, 4–7 kg and >7 kg. We were the ones to voluntarily increase the requirement to 8 kg and more.

We also prefer pole and line fishing for tuna using a hook and a line; therefore, one fish is caught at a time. As this method is more environmentally friendly, the quality of the tuna is better once caught. It preserves all its flavour, quality and freshness.

La belle-iloise must therefore keep an eye on how fishers go about their business: the equipment they use, where they make their catches, which season, and monitor official quotas such as the total allowable catches (TAC) defined for each species in each major fishing area set out by the FAO*. Environmental organisations such as WWF and Greenpeace have identified them as areas to watch, and we respect this.

Sources:

* X World Tuna Conference, Vigo, Spain, FAO, September 2021.

** Indicative bibliography:

Storia naturale di Sardegna: Anfibi e pesci di Sardegna, Francesco Cetti, Florence, Italy 1777.

Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la nature : Ichthyologie, Pierre Joseph Bonnaterre, Paris 1788.

L’Histoire naturelle des poissons, Georges Cuvier and Achille Valenciennes, 22 volumes published between 1828 and 1849 in Paris.

*** FAD: Fish aggregating device, which some fishers use to catch large volumes of fish in one haul. This practice has come in for sharp criticism from the environmental organisations WWF, Greenpeace and the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF).